Theatres of Empire: The Wellcome Collection’s Medicine Man gallery

By the year of his death in 1936, the pharmaceutical entrepreneur, philanthropist and collector, Henry Solomon Wellcome, had amassed a collection of objects five times larger than that of the Louvre. Intending to create a historical museum that left no aspect of medical culture untouched, Wellcome collected compulsively, sending agents across the globe and exploiting the routes and relationships opened up by the British Empire. As Ken Arnold (Head of Public Programmes, Wellcome Collection) noted, Wellcome's collecting was "absolutely a colonial project".

One of the Wellcome Collection's permanent exhibitions – Medicine Man – draws on this vast and varied collection to create a contemporary cabinet of curiosities. Framed by an understanding of the history of medicine as broad as Wellcome's own, the exhibition displays objects as diverse as Florence Nightingale's moccasins, a Bhutanese skull mask, a 17th-century Chinese acupuncture figure and a wood and ivory model based on Rembrandt's "The Anatomy Lesson." The exhibition encourages active engagement with material culture through the display and juxtaposition of curiosities, and emphasises the various stories that can attach to each by providing multiple commentaries for a select few objects. As Ken Arnold, who co-curated the exhibition, explained, the curatorial team wanted to stay "true to some of Wellcome's ideas" and intentionally played on the double meaning of 'curiosity' as both an object and an attitude. But does the exhibition make visible the colonial conditions of Wellcome's collecting, and what role do photographs play within this?

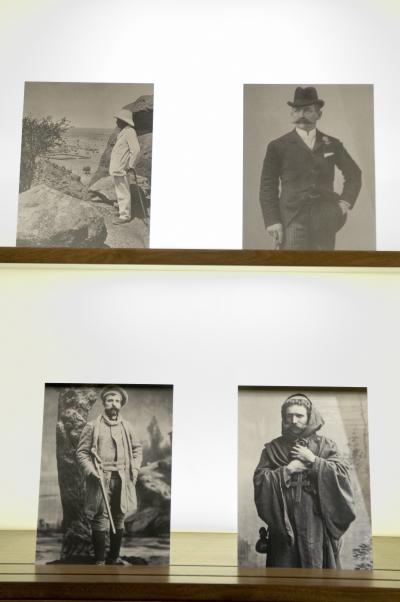

On entering the gallery, the visitor is presented with a number of photographic portraits of Wellcome. Thereby, the biography of Wellcome and his lifetime of collecting provide an organising principle and point of commonality for the disparate displays of curiosities. We see a studio portrait of Wellcome in a monk's costume, complete with false tonsure, from 1885; in another from the same year Wellcome is shown in a shooting outfit; and, among these images, we see also Wellcome in the Sudan in a light-coloured suit and pith helmet on the north-west terrace at Jebel Moya, circa 1913. Ken Arnold reflected that this image, with Wellcome assuming an authoritative and commanding perspective over distant buildings and people, seems typically colonial.

Indeed, Wellcome first visited the Sudan in 1900, two years after the Khalifa were defeated by Kitchener and British rule established. While visiting the battlefield at Omdurman, Wellcome retrieved a number of skulls which he donated to hospitals, universities and museums in Britain to aid in the project of scientific racial classification. Subsequently, Wellcome conducted archaeological excavations at Jebel Moya between 1910 and 1914 where, ambitiously, he believed he might be exploring "the veritable birthplace of human civilisation itself". Wellcome's time in the Sudan was conceived as a philanthropic "mission" to teach "the natives [...] the benefits of our civilisation, and the advantages of truth, honesty, right and justice".[i] All local men who wanted work were found some to do, so long as they agreed not to drink alcohol.

But the image of Wellcome in Jebel Moya is not put to work to excavate the collector's sometimes gruesome entanglement with colonial violence, nor to examine his problematic paternalism and the asymmetric power relations that make such benevolence possible. Rather, the photograph evokes a colonial fantasy that seems to be contained safely within the romance of Victorian eccentricity. Given within the same aesthetic order as the studio portraits, it becomes difficult to see Wellcome's clothing and helmet as anything other than one of so many theatrical costumes, with the landscape of the Sudan substituted for the studio backdrop. In this selection of images then, a difficult colonial narrative is elided in favour of indulging the pleasures and playfulness of Wellcome's collection.

In a gallery that does much to encourage active engagement with material culture and to stress how any single object might be used to tell a multitude of narratives, this display of portraits raises the difficult ethical question of what work photographs produced out of a colonial past might be put to. Ken Arnold reflected that in curating the gallery "colonial politics were sidestepped, hand on heart, in favour of aesthetics", but also commented that a "postcolonial view on the gallery feels entirely appropriate" and hoped that postcolonial critique formed part of gallery tours.

Matt Mead

[i] Quoted in Larson, An Infinity of Things, 49.