The Colonial Album: an Exhibition Case at Pitt Rivers Museum

Creating an exhibition at the Pitt Rivers Museum as part of the PhotoCLEC research project gave me the opportunity to curate photographs and to anatomise the process, from thinking about how selections are made to the challenges of interpreting the photographer’s intentions for the photographs and how this might be expressed.

Conscious of the ways in which the historicity of photographs themselves is often overlooked in museum practice, I wanted approach the process of making the exhibition ‘materially’, working through the photographs as objects in their own right as see what they could tell us.

After working through the collections database at the Pitt Rivers Museum and then on selected parts of its photographic collection, it was clear that thinking about the albums in this way presented a unique opportunity to explore the complexities of ‘colonial photographs’ . The albums could not be as easily categorized as individual photographs. They retained their integrity as objects, and thus their narratives, within the collection.

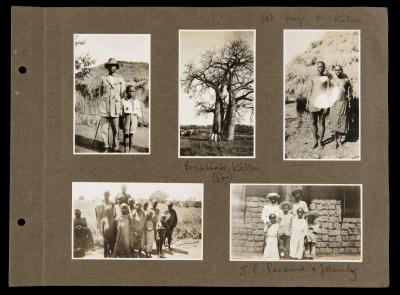

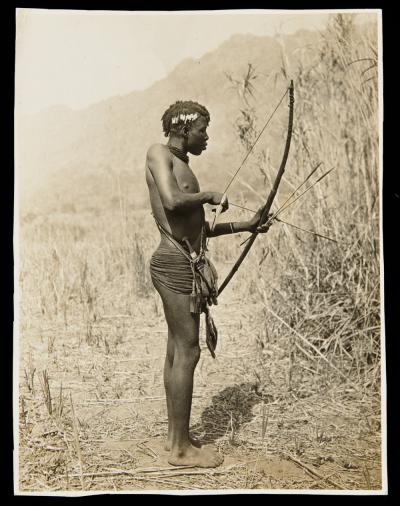

The purpose of the display was not just to show a unique collection of photographs but also to demonstrate various ideas about the presentation of a colonial narrative; to aid alternative interpretations and encourage enquiry into the photographs and the album. The albums of Ernest Douglas Emley, Percy Coriat and William Henry Freer Hill were chosen precisely because they raised questions. Although I had purposely chosen a geographical focus on Africa, the differences in character between the albums stimulated discussions around exhibition, display, and colonial experience. Consequently I conceptualised the albums as representing three sub-themes; the domestic, the political and the aesthetic, as these appeared to summarise the different responses to the colonial experience by their makers.

The display was therefore divided into three different kinds of colonial experiences. This was important because I was keen to suggest the multiplicity of colonial experience and the ways in which photography was used to communicate variously personal, political and relationships with other cultures. Thinking about the different purposes of the photographs and the photographer’s intentions complicated our understanding of the colonial experience for both the colonializer and the colonialized.

Treating the photographs as objects also included the use of history files for the provenance of the albums. This not only enhanced the understanding of the purpose of the photographs but indicated how understandings might change over time. For example captions that may have been added later from memory, or, in the case of Hill’s album, enlargements made from negatives and interleaved into the album for aesthetic reason perhaps. Despite surface similarities the photographs were being asked to do different things.

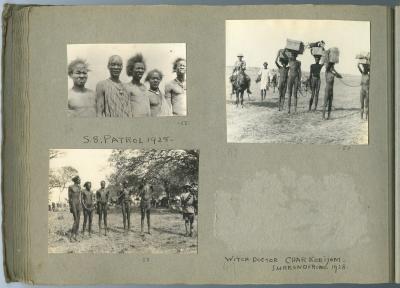

Highlighting the challenges faced by museum curators, regarding photographic collections and colonial histories, became a building block of the case display. The actual discussions of the photographs within each album provided much of groundwork for the display text. For instance, a missing photograph of what appears to have been a violent confrontation in Coriat’s album initially presented itself as a dilemma.

How had it been removed ? By whom ? What does its absence indicated ? How can curators address material of a politically sensitive nature? All these considerations were core to the discussions, informed by both the content and the material qualities of the historical object.

Finally my approach was influenced by the position of the case itself in the institution. The case is situated in a corridor between the Photography and Anthropology Study Centre, and the public spaces of the Museum. The aim of the display was to connect aspects of these two spaces, putting research thinking and the kinds of questions raised into space for the public to think about. It is not easy material necessarily, but material which is often hidden in museums.

The experience of developing the display, working with the Pitt Rivers Collection, and especially these three colonial albums provided an essential education for me, as a young museum professional, on the importance of the way curators ‘think’ with their collections. The anatomical approach extended the understanding of the photographs, the nature of their history and, of course, the importance ‘the colonial’ within the image. The experience also highlighted the importance of unpacking what might be seen in a photograph, and also the importance of the museum’s commitment to provide such a space when working with photograph collections.

http://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/colonial_album.html

Jaina Mistry