Kettles of Cochran

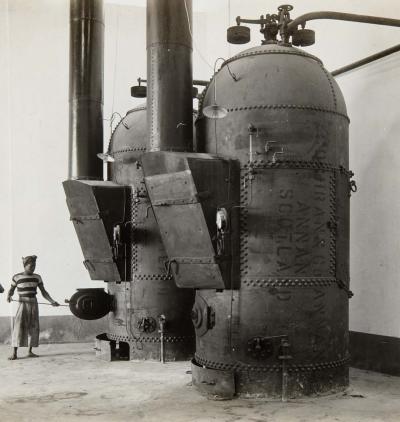

This photograph of two large industrial kettles, and a man firing them up, is an ‘eye-catcher’ in Photographs of the Netherlands East Indies at the Tropenmuseum. It was selected for the chapter on corporate photography in this book which discusses the museum’s Netherlands-Indies photographic collection. The photograph has a vivid clarity and the composition of man and machines stands out. The man is miniaturized next to the gigantic curved and shiny kettles of steel.

The comparison with its ‘original’ in the Tropenmuseum collection reveals why this image has such an impact. Other machinery to the left and right as visible in the original photograph has been removed. The composition of the cropped image is stronger, emphasizing aspects that are less prominent in the full photograph. Neither the author of the book chapter, or the graphic designer, approached the photograph as a museum object. The cropped photograph became a work of art; a carefully composed object in which form and expressiveness are more important than documentary value. However, as such it is published in an account on company photography and colonialism.

Since the early nineteenth century the colony of the Netherlands-Indies was approached by the Dutch as a colony for expoitation, to be economically developed for the benefit of the mother country. Exploring and subsequently developing the Indonesian islands originated in a drive to exploit the country’s riches in terms of natural resources and cultural goods. It was only at the beginning of the 20th century, that within this profitable scheme the so-called ethical policy was implemented. It aimed at the development of a modern colonial state, with the local population benefitting from education, health care and improved infrastructure. Before 1870, all large-scale commercial exchanges between the colony and the mother country were executed under government supervision. Afterwards, the colony was opened to private entrepreneurs.

One such enterprise was the coconut oil factory NV Oliefabriek Insulinde, producing vegetable oils for human consumption. The ‘man with the kettles’ refers to the economic development that marked the relationship between colonizers and the colonized. The photograph can be read as a metaphor: a local worker feeding two large foreign machines which were ever-demanding of fuel. The man fires the kettles of Insulinde’s oil factory Keboemen in Bandung, Java. Iconic as well are several aspects in this photograph that show the interconnections between Europe and Indonesia. We can read that the kettles were manufactured in Annan, which is in south-west Scotland. And we see that the barefooted man is wearing a European-style t-shirt with wide white trousers, probably a celana or Indonesian type of trousers. On his head he wears an iket kepala, a head cloth, probably made of batik cloth. This juxtaposition within this photograph of the agency of colonizer and colonized on different levels, creates a narrative. It probably was carefully staged, the man fixed in a set pose. For “real” work, his position would have been more strenuous, more dynamic.

Although the representational or indexical value of this single photograph is very important in its general validation, other experiential aspects need to be taken into account as well. This particular photograph was part of a factory album.

Tropenmuseum inserted this chapter on corporate photography in the collection book, since it is an important genre in its collection. In Netherlands-Indies company culture it was a common practice to offer people who left the factory (and often also left the colony) a photograph album about the firm. The kettles photograph belongs to such an album. It sits next to other photographs of interactions of spaces, objects and people in and outside the factory selected to represent company memory. Who chose the images and what were the criteria? How do the photographs reflect colonial “reality”?

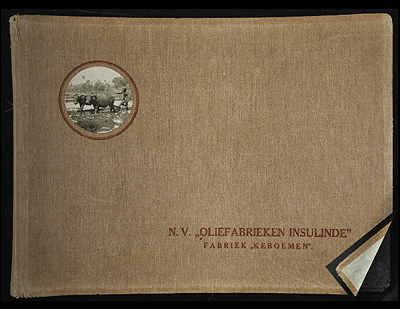

The compilation of the album may have been the work of the photographer, J.H. Austermüller, who had a photograph studio in Bandung. When examining the carefully selected arrangement of photographs in the album, the processing of kopra into oil appears as a rather clean process. No dirt, no dust, or smear can be seen. The largest contrast, however, is created by the image on the front of the album. It shows another iconic colonial Indies representation of the Netherlands-Indies: a farmer encouraging his water buffalos to work the land. Not the specific oil factory decorates the cover; instead, a collective image of the European colonial experience is projected onto the enterprise.

The factory album, together with all the photographs in it, forms a part of the photographic collections of the Tropenmuseum. This album has its own history, but to understand the genre it is important to know that the Tropenmuseum was the former Colonial Museum. It was founded by the colonial entrepreneurs and politicians, who built factories overseas and dedicated themselves to collecting and presenting their work in the colony to the people “at home” in the mother country. The first collections of the Tropenmuseum all concerned products from Dutch colonies. “Corporate photography” as a genre became an integral part of strengthening the economic ties between the colony and Europe.

There is more to a photograph than meets the eye, and one image contains loads of differently relevant stories. What I find interesting about this photograph for example, but what goes beyond the scope of this framing, is why the kettles were imported from Scotland, and not, as most machinery those days, from Germany or from Dutch machine factories. Following the kettles, like following the photographs, would also throw more light on the European colonial connections back home, and how they interconnected.

Daan van Dartel