Infrastructure in West Africa at the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum

This panel, from the now-closed British Empire and Commonwealth Museum in Bristol, explores the expansion of the railways in parts of Africa dominated by the British Empire. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the British oversaw the development of infrastructure throughout African territories with the intention of exerting greater economic and political control. The construction of railways was often motivated by the logistics of Britain’s wars with local populations resistant to colonisation. The same infrastructure subsequently facilitated the exportation of raw materials, carrying minerals and other goods from the interior to ports. Similar projects were undertaken by competing European powers across the continent. By the late 1930s, Africa’s transport networks were contributing to decreasing mortality rates through the better distribution of food; but such benefits for local populations were slow to develop.

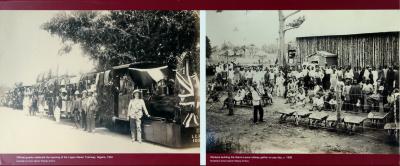

By juxtaposing an image of official guests celebrating the opening of the Lagos Steam Tramway in Nigeria in 1902 with a photograph of railway workers gathered at a work site somewhere in Sierra Leone on payday, circa 1900, the exhibition foregrounds how Empire was differently experienced by colonizer and colonized. The panel makes visible how constructions of race and class positioned individuals unequally in terms of social and economic opportunities.

Shown here, as they were in BECM’s galleries, without heading or detailed text, the chosen images are made to work hard and the museum visitor asked to think for her or himself. In the Lagos image, recognisable signifiers of Empire are framed through the official photography of the Crown Agency. A quietly triumphant vision of Empire is signalled by a string of Union Jacks decorating engine and carriages, while the hierarchy of those present is expressed by who stands where, by who is clearly visible and who is not. The photographer’s intention seems clear: the Empire is represented as a force for modernisation and progress. But while the railways became the paradigmatic symbol for modernity in the Europe of the nineteenth century, the railways in Africa were built not to industrialise the continent, but to draw natural resources to the coast, and from there to Europe. Such projects formed part of Britain’s self-declared ‘mission’ to ‘civilise, commercialise and Christianise.’ Such paternalistic imaginings now seem problematic at best. Nevertheless, the image of the Tramway inauguration coincides with such benign visions. Careful curatorial control is required to ensure this image does not lapse into a nostalgic view of the British Empire, and this is achieved in part by juxtaposition with a second image.

In the image made in Sierra Leone, where the British first began the project of railway construction in Africa in the 1890s, we see dozens of men gathered behind the fence of the site offices. This is a less formal, but still official image, and like the first was donated by the Crown Agents’ Railway Archive. What this photograph cannot show, but only hint at, is how, in constructing lines from mines to ports, British powers chose to ignore the needs of dependencies; or how subsistence farmers were often forced into labour as a way of commuting taxes imposed by the British; or how death rates of those forced into labour, where such figures were recorded, were between 100 and 150 per thousand, resulting from a combination of malnutrition, disease and strenuous work. Such absences often prove to be the limit of working with an official archive.

However, the pairing of these two photographs, taken only two years but one thousand miles apart, is bold enough to signal the clear inequalities that clustered around ‘race’ and class, the colonizer and the colonized, in British West Africa at the beginning of the twentieth century. Without the story of one image being reduced to the story of the other, taken together the two photographs suggest the power dynamic of a particular moment and thus move beyond the specificities of each image. Indeed, it is a narrative of power that was developed throughout the museum’s permanent exhibition. This sense is enhanced by the chance compositional similarities of the images, with the angle of the train and clustering of white dignitaries in the first substituted for the lines of fence wire and group of black workers in the second. In particular, the row of wheelbarrows in the second image which replace the railway carriages of the first emphasise the friction between the signs of labour in the one and pomp in the other. While these similarities might be coincidental, the grouping of images is not. In this example then, curatorial intentions expand the possibilities of the images. While the official status of these photographs is not interrogated, images made on behalf of the Crown Agency are nevertheless used to foreground some of the inequalities of Empire.

Matt Mead