Ethnographic portraits

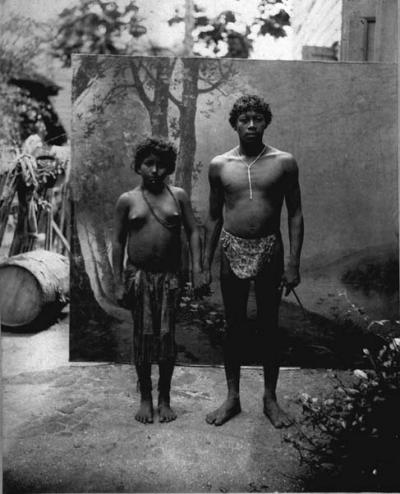

This photograph of a Carib Indian Surinamese couple was made between 1885 and 1895 in the open air studio of Julius E. Muller in Paramaribo, Suriname. It was one of the 300 portraits on display in the 2003 exhibition “Rare Snuiters” (Queer Customers), curated by Midas Dekker, in the Nieuwe Kerk at Dam square in Amsterdam. Midas Dekker is a Dutch biologist, well-known for the way he explains the wonders of nature to a broad audience. Invited to make a photograph exhibition, he choose to reflect on the human diversity. In the past, he had written in the introduction to the Dutch catalogue of the exhibition, all foreigners were flat; one only knew them from photographs. The simultaneous emergence of photography and the height of colonialism enabled the Dutch to get to know the world, while staying at home. Photographers, Dekker continues, make you see others through their eyes. Some photographers denounced the person they saw through their lens, another regarded him a noble savage, or saw them as people to be rescued by missionaries, or as a subject for erotic fantasies. And, Dekkers concludes, it took many long years of photography, before from among the strangers an individual came to be seen. By then, the queer customer had turned into a person, the flat image had turned into a portrait (Dekker, 2003: 7).

Based on this statement, Dekker had selected 300 photographs of people strange, misshapen, noble, industrious, poor or erotic, and from all over the world. A number of these portraits were made in colonial contexts, others were more contemporary; their provenance in a wide range of archives reveals the many patterns of collecting discussed in this website. Photographs came, for instance from missionary societies, press agencies, the Photograph Museum in Rotterdam, archives of individual photographers, or ethnographic museum collections. The temporal dimension of photographs was made irrelevant. A photograph by the Dutch photographer Sem Presser made in Kenya in 1958, the Surinamese Julius Muller photograph from c. 1885, or a Netherland-Indies missionary photograph from 1901: all had been selected according to the same idea. They depicted individualized portraits of ‘other’ people – maybe strange people, maybe familiar people, but all very approachable – no “flat foreigners”. And the way they were depicted, Dekker said, informs the viewer as much or more about the fears and ideas of the photographer as about the people concerned.

The biologist Dekker’s approach to racism and stereotyping, with a knowing wink to evolution theory, evoked some debate. What is the work of photographs in an exhibition addressing the very topic of photographs’ own history of stereotyping? In the case of the young Surinamese Carib couple posing in front of the backdrop of a forest, it was their posture, together with the frame of the photograph that does not cover the full background of the picture but shows the context of Julius Muller’s open air studio in Paramaribo, that supposedly turned the photograph into a primitive image of noble people. However, the a-temporal presentation in the exhibition – the typecasting as noble savages as Dekker saw it – did not reveal, that the photograph is part of a series with which people in Suriname literally had aimed to present their society to the people of the Netherlands. The same little bush in the front of the photograph also appears in the portrait of a Chinese family, a group of Javanese male and female indentured labourers, a group of Hindustani men, or women, an Afro-Surinamese woman in a koto missi dress and others, photographed against different backdrops. As a series these Surinamese portraits by Julius Muller have a long history of collecting, exhibiting and reproduction. By selecting one in the context of queer customers, the photograph was made to work in another way than had been the intention of the sitters and the maker. That is not a unique procedure. Typecasting often happens at a long distance from actual encounters. And that was maybe also the point Midas Dekker wanted to make. However, meanwhile he repeated the process of creating a new context for once individualized portraits that now became generic.

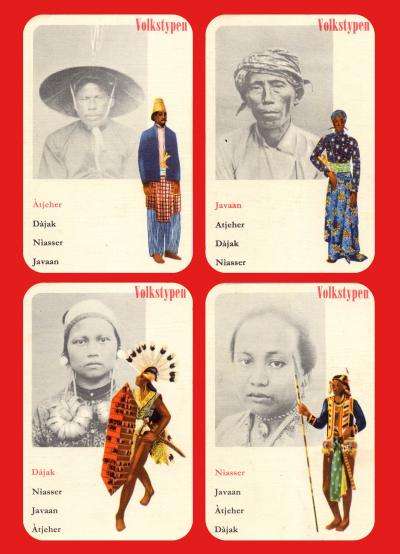

We can compare this with another example of how in Europe, at a distance of actual encounter, individualized portraits were made into generic types. In 1941 game producer Hausemann and Hötte N.V. Amsterdam issued a pack of cards edited by the Colonial Institute. It was a period when The Netherlands was under German occupation and the Netherlands-Indies was soon to be invaded by the Japanese. In twelve sets of four, the playing cards presented a miniature categorization of Indonesian nature, the people and culture. In a letter send to schools, the Colonial Institute explained that this game would help the people to feel a little bit closer to East, in these uncertain years.

One set of cards shows four Volkstypen (ethnic types): an Acehnese and Javanese man; a Dayak and Nias woman. The blanked-out photographs turn the people into culturally – as well as racially – isolated ‘objects’ with no obvious relationship to time or place. Embedded as the playing cards were in the photographs collection of the Colonial Institute, however, we easily could retrace each ‘original’ picture. This lead to portraits that reveal various moments of encounter between photographer and sitter. The Dayak woman, for instance, was portrayed in Apo-Kajan, in 1919 by J. Jongejans during an expedition to Central Borneo. In his travelogue on “life and environments of the head hunters”, Jongejans explained that the woman was willing to pose in front of the camera after he had shown the villagers other photographs made during previous expeditions, as well as a photograph with his own wife and children. Her anthropological blanked-out portrait on the playing card, produced twenty-two years later as a static essential image of any Dayak woman, reveals the processes of distancing through the use of ethnographic photography. Photographs like these also were turned into postcards; sometimes, as in the case of the Surinamese ‘ Eunubia’ (beautiful black lady, a photograph of a Hindustani woman that has been endlessly reproduced ), the sitter even got a fantasy name that stressed the stereotypical meaning of the image.

Jongejans made this woman’s portrait against an improvised backdrop of just a piece of cloth. Together with the other photographs of this encounter in the Tropenmuseum collections, it provides an impression of how photographs came to work as fieldwork notes in a mix of cultural and physical anthropological research. Framing through creating a backdrop enabled the viewer to concentrate on the cultural specificities of the person in front of the camera. Maybe this is also one of the explanations why anthropological museums today seem to have so much difficulty in overcoming the categorizations that they helped shape

Susan Legêne