Margit Ellinor’s still lifes

The Sámi Collections (RiddoDuottarMuseat-Sámiid Vuorká-Dávvirat) situated in the community of Karasjok in Northern Norway, was established in 1972 as a part of the political and cultural mobilisation and struggle of the Sámi population. This Sami museum is not only a cultural history museum. It is also a museum that has built up a considerable collection of contemporary art by Sámi artists. Walking through this art exhibition, one cannot help noticing that photography appears to have assumed something near to a dominant position. But how do Sámi contemporary artists seek to establish new modes of historicity through photography? How do they speak about forgotten places and forgotten identities? The work of artist Bente Geving furnishes a good example of such photography-based Sami contemporary art.

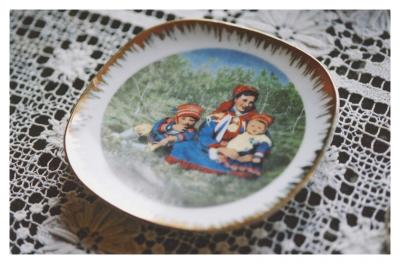

In a work titled Margit Ellinor, the photographer Bente Geving, born 1952, presents a series of small kitsch still lifes from a coffee table – many of which with prominent Sámi imagery. One of her photographs is, for example, a close-up representation of a gold-rimmed porcelain plate placed on a white tablecloth. The plate is in itself decorated with a photographic reproduction in washed-out colours: a ‘tourist’ image of a beautiful young and smiling Sámi mother with her children. The happy little family is posing in a natural setting surrounded by green grass and mountain birch trees.

On one level it is tempting to read Geving’s photographs of decorative objects as an intimate portrait of the person who arranged them, the artist’s mother, Margit Ellinor, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2001 and died in 2007. This understanding also seems to be in line with by the artist’s own statement about the work: “I started to photograph my mother’s room in 2002. At that time she had begun to rearrange images and decorative objects, bringing forth things that had been stuffed away in drawers and cupboards, while removing others. She decorated and combined different objects on tables, on shelves and in cabinets. She did small changes – and moved things around. Every time I visited her there were new constellations and arrangements. I became fascinated by the colors and her compositions – and also interested in going into her world to make my pictures out of her pictures. It became important. She said it was her work.”

Mass produced Sámi images of the past are in this way not only appropriated, but also transformed into what Geoffrey Batchen has termed “personally charged material objects which induce the full, sensorial experience of involuntary memory” (Batchen 2005). In this way, Bente Gieving’s work could also be seen as an example of Siegfried Kracauer’s understanding of photography’s ability to anchor the present tense of things past so that their cultural meanings can be explored (Barnouw 1994:31). The artist uses photography, not to replace (failing) memory with sharp images full of information. Rather she enhances her mother’s memory work through photography by adding new layers of meaning. The close up photograph of the porcelain plate carries allusions to the act of touching of touching history. And the slightly unfocused foreground of the photographic image of the still life may in itself be seen as a reflection of the near-sightedness inherent in memory processes – and the sense of crisis connected to it. The photographs of Margit Ellinor’s kitsch installations where Sami souvenir imagery is used as raw material, thus becomes an arena for articulating a sense of memory loss – not only on a personal, but also on a broader, collective level. Ultimately they therefore seem to speak about repressed cultural identity – in a museum designed exactly for this purpose.

Sigrid Lien