Visual nostalgia

Photographs from the colonial past take a foremost position in nostalgic forms of postimperial remembering. The term ‘nostalgia’ is a Greek compound, consisting of nóstos (to return home) and álgos (pain, ache); but these apparently ancient roots hide more contemporary origins. It was in 1688 that the term was first coined by Swiss doctor Johannes Hofer after observing the condition of Swiss soldiers who in the plains of France and Italy were pining for their native mountain landscapes. Diagnosed as a medical pathology, nostalgia could lead to desertion and serious disease to the point of death. Gradually, the meaning of nostalgia has shifted and expanded. Nostalgia has mutated from a geographical malady into a social and cultural phenomenon which, in the memorial culture of contemporary western societies, can denote melancholic pleasure. In common parlance, nostalgia refers to notions of lost innocence, beauty and apparently simpler times.

Since the 1970s, a postimperial memory industry has proliferated in the west. Triggered in part by the effects of changing demographics at home and the processes of globalization, the aesthetics of nostalgia have become an alluring and fascinating subject in western societies such as the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. The revival of nostalgia for the imperial period refers to a diverse range of material and immaterial phenomena, such as objects, activities, styles, tropes, texts and (moving) images mediating the forgone colonial era. Black and white photographs, faded or not, take a foremost position in the nostalgic construction of an idyllic colonial past. In the Netherlands, the continuing (post)colonial relationship between the Netherlands and its former colony has generated a wide and on-going range of intricate and conflicting cultural memories. Often drenched in nostalgia, such imaginaries testify to the ambivalent fascination the East-Indies exercises in the postcolonial Netherlands where the beloved colony to this day has retained a constant visual presence in the national imagination.

The Dutch postimperial revival of nostalgia has largely emerged through visual forms such as film, TV and specifically colonial photographs, beginning with family photographs brought from the colony by Indies-Dutch migrants of mixed descent. From 1958 on, Indies-Dutch spokesman Tjalie Robinson, in his magazine Tong Tong, started a massive public sharing of these migrants’ family photographs. Such enactment of remembrance was most important in the construction of identities and communities through which the Indies migrants made sense of their lives in relation to others. On the other hand, the relocation of their family pictures from personal to public memory marked the beginning of a wider circulation of colonial photographs in the Netherlands.

In 1961 Rob Nieuwenhuys compiled and published his well-known book Tempo doeloe: Photographic Documents from the Indies, 1870-1914 and later extended it into three books in the 1980s. These melancholic photo books were widely distributed and highly praised by the white Dutch elite as if the Netherlands-Indies were ‘discovered’ for a second time. They contributed to the rise of a pervasive postimperial mode of nostalgia, which came to be known as tempo doeloe, meaning ‘the good old days’ in Malay. Tempo doeloe nostalgia refers to the Netherlands-Indies recast in an idyllic light. Unspoiled by modern technology, life in this aestheticized colony is pleasant and ‘innocent’; men are still men, women are still women and the natives know their place. From the 1970s on, tempo doeloe nostalgia has had a great impact on the memorial culture of the Netherlands, even when in 1969 public accusations of war atrocities collided with the nostalgic memories already in circulation and reactivated shameful discourses about violence, exploitation and racism in the colony. However, nostalgic and guilt-ridden discourses have always been effectively separated in the Netherlands. As a mode of national memory, tempo doeloe nostalgia has continued to offer every Dutch citizen a pleasant and innocent format to deal with the uneasy loss of the East-Indies. The recent digitization of many colonial photographic museum collections has created technological data banks of thousands of free-floating colonial images that can be shared by everyone. Even without materially being present, digital photographs of the Indies have become visual witnesses of a colonial reality that simultaneously has become a controversial and a nostalgic past.

By contrast, in Britain, the nostalgic remembrance of the colonial past has generally absorbed feelings of guilt, and particularly defeat, to produce what Paul Gilroy has described as a condition of ‘postimperial melancholia.’ Throughout the 1980s, nostalgia for the British in India was expressed in film and literature, and epitomized by the image of the colonizers at rest on the veranda. But nostalgia is an unsuitable form with which to cope with a history as complex and as problematic as that of the British Empire, even if the aim of remembering is to create a comforting representation of the colonial past. Thus, ‘postimperial melancholia’ provides the British with a form of remembering that is certainly nostalgic, but also expands so as to be able to accommodate questionable, and even reprehensible, historical figures and events. In short, ‘postimperial melancholia’ positions the British as the victims of their own best intentions.

A useful example for exploring the structure of postimperial melancholia in British heritage culture would be the statue of Henry Morton Stanley that was erected in Denbigh, Wales, in March 2011. Statues are a celebratory form and the statue of Stanley is undoubtedly intended to commemorate the life of Denbigh’s most famous son. However, an uncomplicated celebration of Stanley is of course compromised by his well-known role in colonial atrocities in the Belgian Congo. Thus the statue figures a very human Stanley, without a plinth, pith helmet at his side, a hand outstretched to welcome visitors to Denbigh. Stanley is represented as a product of his time and as such a figure still worthy of commemoration, albeit in a melancholic tone.

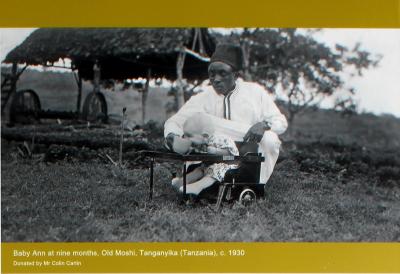

Curators in British museums working with photographs from the colonial past have to contain and control many of the same nostalgic tropes as their Dutch counterparts. The photograph shown here is taken from the permanent exhibition of the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum, Bristol, and shows a male servant feeding his employer’s baby girl in Tanzania, circa 1930. Although the photograph reveals nothing of the relationship between the two, the image might easily be read as a tender one. The pastoral scene, the signifiers of family life and the apparently placid servant all fit comfortably with a benign vision of colonial life. However, the exhibition text mitigates the affect elicited by a nostalgic reading of the image. The photograph is reproduced on an exhibition board entitled "Innocence Lost" which treats the relationships between colonizing-employer and colonized-servant without sentimentality. On the exhibition board which immediately follows, the text resists nostalgic readings, insisting that while "[s]ome employers grew very fond of their servants […] they often did not see them as responsible adults [and] thought of them more like children who needed training."

Precisely because of the allure of these kinds of images, visualized nostalgia has been sharply condemned by many social critics for representing false and inauthentic histories. However, nostalgia cannot be an intrinsic quality of the content of an image; rather, nostalgic readings reflect broader cultural conditions. As ‘mediated memories’ visualized nostalgias are produced and appropriated by means of media technologies for creating and re-creating a sense of past, present, and future.[i]

Recently, the specific social functioning of nostalgia has therefore become the object of analysis. Many scholars have begun to approach nostalgic thinking as a force that complicates rather than simplifies.[ii] For instance, Svetlana Boym has drawn a useful distinction between ‘restorative’ and ‘reflexive’ forms of nostalgia. While the former is reactionary and trades in a hopeless desire to restore an imaginary past, the latter can be playful and ironic, and function in the knowledge that all representations of the past are constructions of a sort.[iii] As a much earlier example, the philosopher Walter Benjamin invested nostalgic visions of premodern communities, real or imagined, with a critical potential; this could be usefully harnessed to reassess that in modernity, and particularly that associated with technological progress, which is at odds with social justice. Pointing out nostalgia’s ‘critical potential’ for distinct memory communities can thus re-contextualise nostalgic images for processes of identification in diverse memorial cultures.