Photographs in museums beyond multiculturalism

From the edge to the center: the photograph collection of the Museum Maluku

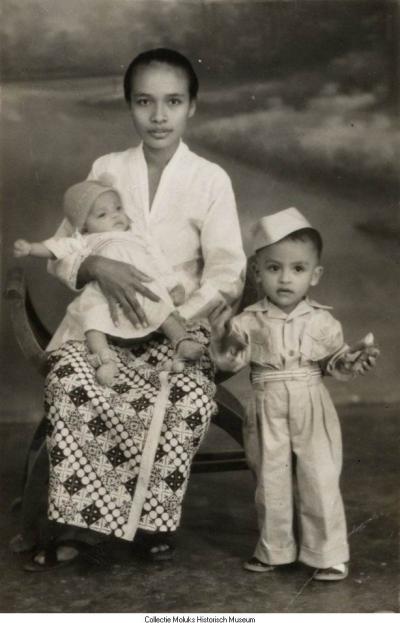

This picture of a woman, spouse to a Moluccan soldier of the Royal Netherlands-Indies Army (KNIL), and her two children belongs to a genre of family portraits that were common in the Netherlands-Indies, where pictures were made to be sent to relatives, living in faraway places. This particular picture was part of a gift of photographs and documents by the relatives of a former Moluccan minister, the Reverend J. Keiluhu.

Keiluhu travelled widely within the community, as was reflected by his photograph collection. At the time of his donation to the then Moluccan Historical Museum (Museum Maluku today), no names or additional information were available. When a large part of the photograph collection of the museum was digitized for the Royal Library’s databank “Het Geheugen van Nederland” (The Memory of the Netherlands) this picture was included as well. The caption just read: “A KNIL wife and her two children”.

As the museum looked for additional information on its photograph collections, one of the means employed, was physically putting up a panel with photographs in the museum, and asking the help of visitors to identify people and places. It turned out to be an effective way to involve the community. In this particular case, the family was identified as the Rahajaan family who had migrated to the Netherlands and used to live in the city of Zwolle. Not only information on the names of Mrs. Rahajaan and her two children was given, the museum also learned that Mrs. Rahajaan had repatriated to Indonesia. As a result, the caption to the entry in “The memory of the Netherlands” could be updated while also adding the picture of Mrs. Rahajaan to the website “De Aankomst”(The Arrival), listing the names of some 12.500 Moluccans that belonged to the immigrants that arrived in the Netherlands in the first half of 1951. (http://aankomst.nationaalarchief.nl/)

The caption now reads: F 99.9557: Studiophotograph of a KNIL-spouse with two children. Mrs. Rahajaan with oldest son Wim and daughter Martha. Afterwards Mrs. Rahajaan went to live in Zwolle and subsequently returned to Tual, Malang, Java, ca. 1950. Collectie: MuMa/coll. J.B. Keiluhu

This is ‘just’ one of many family photographs that moved from the private sphere to a public collection. Often, such photographs from the colonial past are donated to museums because next generations no longer feel connected to the image. However, as this photograph shows, the context of Museum Maluku often provided such images with a new meaning, not only as a genre, but at the content level of the individual image. In this case, the enrichment of the ‘metadata’ of the colonial photograph happened in the context of a museum with strong ties with a specific postcolonial community.

When the Molucan Historical Museum was opened in 1990, it was the first ethnic community museum funded by the Dutch government. The idea of a postcolonial ethnic community museum was still alien to the Dutch museum world so the first response of various ethnographic museums to the initiative was to offer to establish a Moluccan department within their existing museum. The collections of the new museum were mostly obtained by gifts from individuals and organizations that were either from within the community or had relations with it. These consisted of objects, archival material and sometimes also photographs, mostly related to the migration to the Netherlands and the (mostly military) profession of the men in colonial Indonesia.

As the museum became more accepted by, and interactive, with the community, the number of photographs donated increased. In turn, the museum used these photographs to improve the ‘visibility’ of the Moluccan community in the Netherlands. The fact that the photograph collection of the museum consisted mostly of private photographs that were never published before, resulted in a growing interest from news media and other parties. When the Royal Library started to envisage its large scale digitization project through the website “The Memory of the Netherlands” in the early 21st century, the Moluccan Historial Museum was among the first 30 institutions invited to participate. Almost 10.000 photographs, ranging from present day photographs to photographs from colonial times were digitized while the website also included an educational program. In the first year after the collection on Moluccan history and culture was added to the databank in October 2004, it had the most hits of all collections, while in the next year the educational application ranked number one on its respective list. These results seem to corroborate earlier findings of the appeal of digitized heritage information to migrant communities in the Netherlands by the National Archives.

Moving beyond borders

In the beginning donations of photographs were scarce, as members from the community were hesitant to part with photographs considered to be part of their personal or family heritage. This attachment did not manifest itself with regard to objects such as the trunks that were used to hold their belongings when they migrated to the Netherlands. Somehow this changed over time. The appreciation of this material heritage has grown (also because of the use of these objects by the museum), whereas people are more willing to share the images of their family history. Photographs were initially only loaned to the museum, where copies were made; today the original is kept in the museum or by the families, whereas digital copies move free through cyberspace. The terms of usage remains a topic that needs constant consideration. As in the case of the photograph on this webpage, photographs were often donated to the museum by former colonial officials, ministers or teachers who had worked in the Moluccas and donated their albums because they felt their (grand) children would not take interest in them. In time the possession of several albums by different individuals from the same period has enabled to the museum staff to refine the analysis of the photographs by cross-referencing individuals and locations on photographs. Also a specific genre emerged out of the collection of albums: the genre of “farewell-albums” with standardized photographs of iconic views and locations in Indonesia, the former Netherlands-Indies.

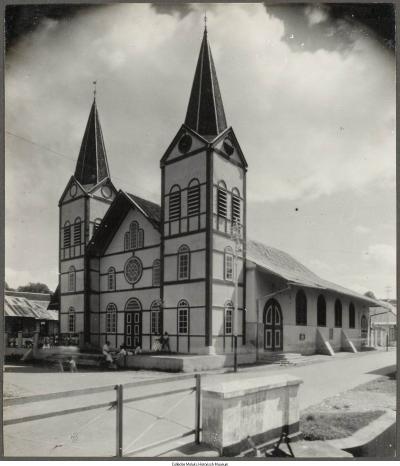

Included in “The Memory of the Netherlands” were also 119 pictures from a collection of a Dutch minister who was stationed in Ambon prior to WO II, the Reverend J. Enklaar. One of his pictures was a postcard of the Ambon’s Main Church which was destroyed by Allied bombings during the Second World War. The picture later surfaced on a Facebook page of a Moluccan journalist based in Ambon in a series dedicated to the history of the city.

Thus, the digitization of the photograph collection of the museum has had a transnational effect, as the photographs are also being explored, used and commented upon from Indonesia/the Moluccas. In such appropriations, often no mention is made of the source of origin of the photograph. They change meaning beyond being a colonial photograph and change context beyond the axis of Dutch/Moluccan relationships.

New meanings

Transnational and intergenerational effects within the Netherlands can also be discerned as photographs from the museum collection are re-interpreted or manipulated. This poses challenges to the museum as it has no exclusive authority nor control over interpretations. As a digital image, the photograph as an object loses its importance to its users; it is the imagery that is seemingly conveyed through the photograph, that mostly matters. Community members feel that they too possess knowledge and authority.

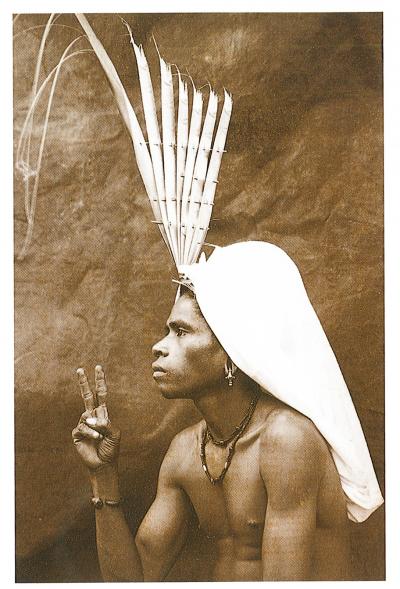

Recent use of the historical picture of this a young man from Tanimbar by the Catholic missionary and ethnographer Petrus Drabbe, is a case in point. The photograph was taken during an ethnographic journey in the 1930th, that was partly commissioned by the Colonial Institute in Amsterdam.

Drabbe used the photograph in his book on “The life of a Tanembarese” (1940). In 1995 a selection of the pictures were reproduced from their original glass plates in “Tanimbar. The unique Molucca-photographs by Petrus Drabbe”, which accompanied an exhibition of the photographs in the ethnographic museum in Leiden. The availability of the photographs led to their reappearance in different contexts. When violence broke out in the Moluccas (1999-2004), the picture of the young Tanimbarese was used in a campaign in the Netherlands accusing the Indonesian military of committing genocide on ‘indigenous’ Moluccans. There was no mention of Tanimbar, nor of the original context of the photograph. And thus the photograph was repurposed to a completely different work.