Photographic Treatments of the Benin 'Punitive Expedition' in Two British Museums

Photographs made during Britain's military presence in Benin in 1897 are displayed in a number of British museums, including the British Museum (London), the Pitt Rivers Museum (Oxford), the World Museum (Liverpool), and the now closed British Empire and Commonwealth Museum (Bristol). As a violent episode in Britain's colonial past, the 1897 'Punitive Expedition,' in which Benin City was looted and destroyed, represents a pressing, high-profile and challenging history for museum interpretation. Unlike much of the colonial past, it is also one that has received critical attention and initiated debates about the ownership of cultural property and questions of restitution and reparation.

But what work are these photographs put to in each institution? And what does the process of selection and interpretation tell us about the priorities of the museum in question? Below, these questions are explored through exhibitions in the British Museum and the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum.

In the British Museum's Africa Galleries, the exhibition boards of explanatory text and images dealing with the 'Punitive Expedition' cannot help but be dwarfed by the museum's display of Benin bronzes. Around 200 bronzes were taken into the museum's collection, more than 50 of which are displayed in the galleries. The exhibition text positions Britain's military action as "retaliat[ion] for the killing of British representatives", not as an act of colonial aggression, but also explicitly describes the bronzes as "booty", foregrounding their removal from Benin as a theft. The photograph which accompanies the exhibition text conforms to the trophy genre, with the spoils of war, including a brass plaque, arranged on the ground in front of the assembled victors. Despite conforming to these stylistic conventions, the image appears casually composed, with a packhorse present in amongst a haphazard mass of pith-helmeted Britons and their African allies. Reproduced at a small scale to accompany the exhibition text, the photograph is not represented as a historical object in its own right; nor interrogated in terms of its conformity to or departure from generic conventions; nor is it considered forensically beyond its superficial historical content. Rather, the image is used to both authenticate the bronzes – the real attraction – and to acknowledge the British Museum's entanglement in this challenging history. However, this acknowledgement falls short of self-reflexive critique. The history that is told elides British culpability in the conflict. Moreover, any debate about the ethics of the continued display of the bronzes in the museum is attenuated by the equivocal exhibition text, which reassures visitors that the "Benin treasures caused an enormous sensation" in Europe, "fuelling an appreciation for African art which profoundly influenced 20th century Western art." The discursive shift from colonial history to the history of art, in which the bronzes are validated by European high-cultural values, elides the political and social tensions of the colonial past and its legacy in the present.

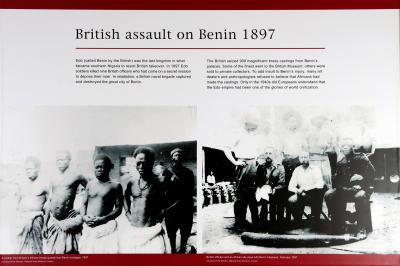

In the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum (BECM), two photographs produced during the 'Punitive Expedition' are reproduced on an exhibition board which recounts the history of the "British assault on Benin". The decision to use the term 'assault' rather than the more common 'expedition' is an indicator of the exhibition curators' intent to reassess conventional narratives of Britain's colonial past. Indeed, the panel text refers to what is now southern Nigeria as 'Edo' rather than 'Benin' in an effort to recover something of the local point of view. This effort to balance the narrative is extended to the conflict itself: the exhibition text does not position the killing of nine British officers by Edo soldiers, which provoked the British assault on Benin, as an unprovoked attack, but acknowledges the local perception that the British officers were on a "secret mission to depose their ruler".

The first photograph accompanying the BECM text shows four "Benin hostages" under guard. The overexposed or faded areas of the photograph and the scratches on its surface work to retain a sense of the photograph as an object, and help to historicise the image despite its transfer onto an exhibition board. Although caution should be exercised in reading what is only the expression of a moment, the furrowed brows and downcast eyes of the prisoners stress their precarious situation and emphasise the human stories in this history. The second image, like the one used in the British Museum, conforms to the trophy genre, although its composition is more formal. Again, the materiality and historicity of the photograph is emphasised by the degradation of the image; it is difficult to make out the faces of those in the back row. The careful containment of subjects in the composition of both images stresses the workings of authority and hierarchies of power in the making of each photograph.

Notably, both BECM photographs depict Britain's African allies: in the first, an African soldier stands erect and alert, guarding the four prisoners; in the second, an African officer sits behind one of the large Benin tusks with two Britons, implying equality of status. The historical complexity suggested in these images, which throughout the exhibition frequently exceeds the tight control of the exhibition text, is typical of the BECM's approach, in which the violence of Britain's colonial past, while not infrequently racialised, cannot be coded through 'race' alone.

Unlike the story of the 'Punitive Expedition' in the British Museum, which is encumbered both by the prioritisation of the 'booty' itself and by the museum's own entanglement with this difficult history, it is people, and the complexity of colonial networks, rather than objects that emerge as central to the BECM narrative. Importantly this is achieved photographically, not simply through a ‘peopling’ of the display through the use of photographs, but rather using the photographs to open up a more complex and critical space. The BECM's distance from the Benin bronzes also facilitates clearer reflection on their place in the history of art, which is itself historicised rather than used as a diversion from the rawness of the colonial past; the BECM exhibition text reports that, after the expedition, "[t]o add insult to Benin's injury, many art dealers and anthropologists refused to believe that Africans had made the castings. Only in the 1940s did Europeans understand that the Edo empire had been one of the glories of world civilisation."